Quilt is ostensibly the story of a man dealing with his father’s death. The death occurs in the opening pages and follows that of his mother two years earlier. In some kind of beleaguered response to these events, the protagonist, with the help of his long-distance girlfriend, installs an aquarium in his parents’ lounge, housing four rays. The creatures become the starting point for metaphysical considerations that seem eventually to detach the protagonist from reality.

The rays are not the first metaphysical fish in literature. Those who’ve read Steven Hall’s The Raw Shark Texts can draw comparison with that novel’s ‘word shark’ and its representation of trauma. Hall‘s novel is a more fantastical endeavour; Royle’s is shorter and more tightly focussed, and perhaps more effective because of it.

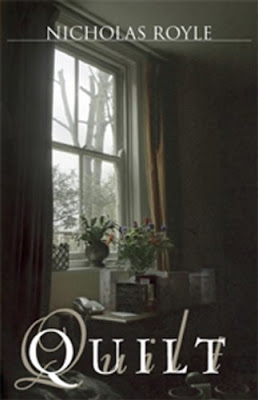

The inside cover image alerts us to a visual comparison to be made between a shoal, or ‘fever’, of rays, and the design of a patchwork quilt, setting up metaphorical possibilities from the outset.

What do we know about quilts? They are domestic and familial, often heirlooms. One tradition sees quilts pass down the female line, each recipient adding or decorating a panel. They are used in times of illness and bequeathed at death. (The famous AIDS remembrance quilt extrapolates these ideas into a vast personal memorial). This all seems to tally with the theme of generations and mortality in Royle’s novel. The prose is also punctuated throughout with the Omega symbol, connoting death and an ending, another thematic link.

In some respects this is a fitting book to complete our unit, relating as it does to a number of other works studied. The significance of the house compares with The Rain Before It Falls. The weird metaphysical angles are reminiscent of Amaryllis Night And Day. The importance of material objects and memory is also seen in The Blindfold. The detachment of rationale, and possible metamorphosis, harks back to The Horned Man.

Language in Quilt is remarkable, the vocabulary is rich and unusual. Early on we come across ‘aporia’, ‘lachrymosity’, ‘analepsis’, ‘lexemes’ – but it’s sometimes colloquial too: ‘gubbins’, ‘clobber’, ‘no-brainer’. Sometimes it’s a great pleasure to read with a dictionary, and this is evidently a novel not just to be read but to be studied, but it has drawbacks. The pleasures of a bold vocabulary can intervene on narrative flow. At times the prose suggests it is not meant for those of us with a less than highly-advanced grasp of the language, even while its themes assert themselves as universal.

But it is enjoyable. Royle uses linguistic quirks such as alliteration, double meaning, rhyme, anagram. The writing is reminiscent of poetry more often than prose, and in some cases of specific poets. These lines from page 5 might invoke Dylan Thomas:

‘…softer, gulping, an immeasurably beautiful strange ancient fish glopping glooping groping grasping rasping for air…’

… page 14 suggests the poet Tony Harrison:

‘What has made it possible in the past between us, to keep away weeping, all these years, is gone. Because it is going it is gone already. In his esoterically Buddhist way, he has always stressed the joys of silence, the turns of taciturnity. To tire the sun with talking and send him down the sky was never an option. Conversation with my father has always been a minimalist art. And from his eyes in all these years unwitnessed, it now occurs to me, even a tear of sadness shed.’

… page 93 might invoke Sylvia Plath:

‘Neither fish nor fowl, they move like moles in the gravel of the substrate, burrowing and blowing up air, like animated pancakes, or stay at rest on the bottom, half-hidden dark moons.’

The protagonist and his father shared a love and command of language and it is the disintegration of this that signifies life or reason ebbing away. In his final days his father is reduced to cliché: ‘These things happen from time to time,’ he says. The protagonist moves from etymology, that is, the breaking down of words, to language itself breaking down. He is misinterpreted and difficult to understand. There is a sense of relief and surety when the narrative passes to his girlfriend, his head and language are confusing places to be.

The novel incorporates numerous viewpoints. Present and past tense are both used, while the narrative moves between first, second and third person, with three characters plus an occasional fourth omniscient voice in evidence. The structure is complex in those terms while the story itself moves simply, if bizarrely, from death to funeral to aquarium. It is the consideration of rays that adds complexity, introduced early on with the phrase: ‘The ray seems to figure what is magical and uncanny about philosophy’. The creatures become a focal point of thought and language, and also perhaps of a literally unfathomable response to death.

We are invited to draw an analogy between the rays and the dead father. The rays are something to be kept alive in a house of death. The father is likened to a fish when he splutters for breath. The tank is likened to his grave as people gather around it. At some point in the novel it occurs to me his father’s name may even have been ‘Ray’. The vicar is said to use ‘the affectionate diminutive version’ of his name; perhaps ‘Ray’ from ‘Raymond’. The name ‘Raymond’ itself appears in the list of names on page 147 with the instruction that it not be shortened to ‘Ray’, perhaps to keep his father’s name separate and sacrosanct.

Incidentally, the rays themselves are named; Mallarme at least significantly and fittingly so, after Stephane Mallarme, the symbolist poet whose work influenced both the Surrealists and the Dadaists.

The end of the novel invites interpretation. Having anticipated the protagonist drowning in the aquarium, not least because of his earlier recital of Clarence’s speech from Richard III (Clarence is murdered by being drowned in a vat of wine), what we in fact discover is a new and larger aquarium in the house containing a single giant ray with the protagonist nowhere to be seen. Whether this is metamorphosis or symbolic substitution, the sheer uncanniness of the vision is a pleasingly perplexing final image. Humanity has been shrugged off in favour of a form that predates language and so predates the anguish of things that might be painfully inexplicable.

1 comment:

This is an excellent and fair assessment of this book, which I read recently. I'm intrigued by your comparisons to Russell Hoban and James Lasdun, both fascinating writers, so I must go off and look at your earlier reviews.

Post a Comment